⚡

WireUnwired Research • Key Insights

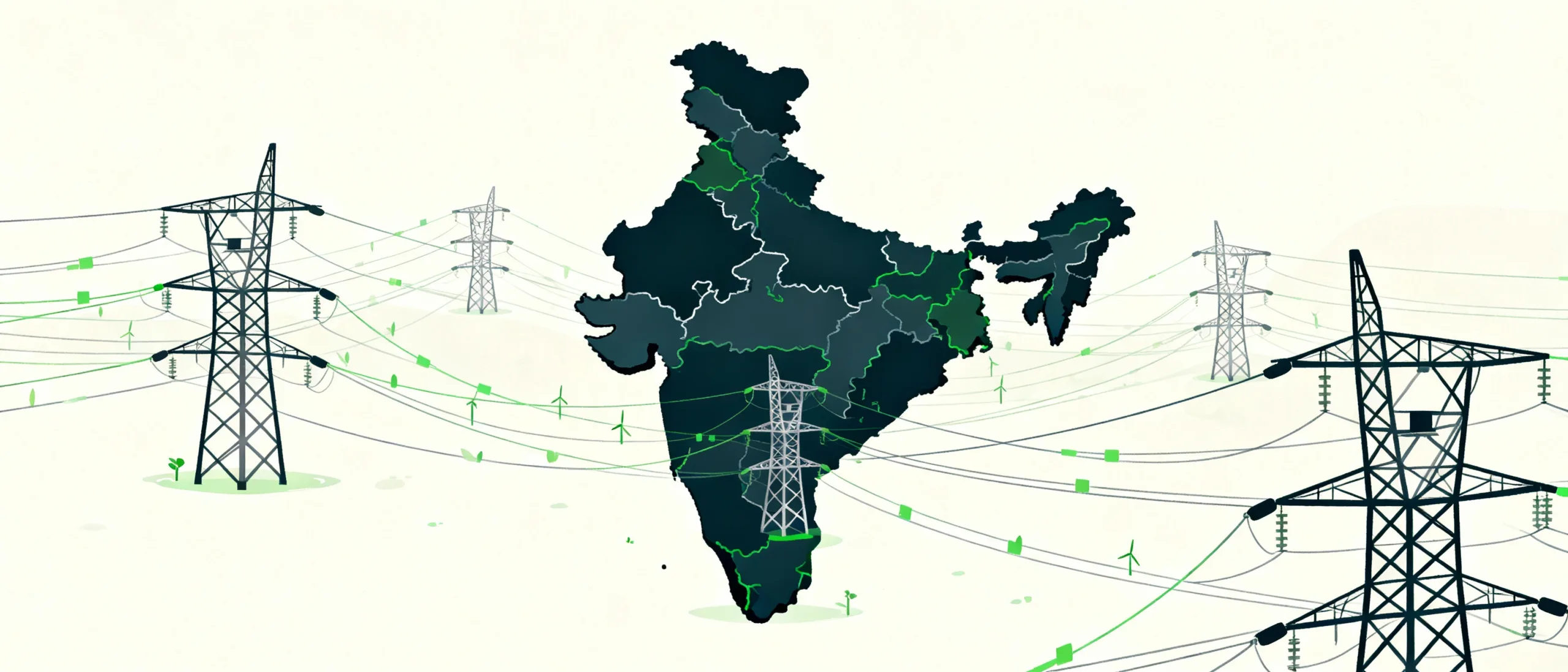

- Breaking news: India has approved a Ladakh–Haryana HVDC corridor with 13 GW of dedicated renewable evacuation and an on-site 12 GWh battery system, one of the largest such integrated schemes globally.

- Impact: The project is a flagship of the Green Energy Corridor Phase II program, aimed at turning Ladakh’s high-altitude plateau into a national clean-power hub while easing transmission bottlenecks that increasingly threaten India’s energy transition.

- The numbers: Around 713 km of HVDC lines (1,268 circuit-km), two 5 GW terminals at Pang and Kaithal, and a total investment of roughly INR 207.73 billion (~USD 2.5 billion), with 40% central support and the rest funded by POWERGRID.

India has just greenlit one of its most ambitious power highways: a high‑voltage direct current link from Ladakh to Haryana, purpose-built to move 13 GW of solar and wind off a remote Himalayan plateau and into the country’s northern demand centers.

The line will not travel alone. It is paired with a massive 12 GWh battery energy storage system designed to smooth one of the most volatile renewable profiles on the planet into something the grid can trust.

What India Has Approved ?

At the core of the scheme is a new interstate HVDC transmission system, to be implemented by state utility POWERGRID under the national Green Energy Corridor Phase II program. According to project details highlighted by Power Line’s coverage of India’s green energy evacuation push, the Ladakh–Haryana corridor is explicitly designed to evacuate 13 GW of variable renewable capacity from a high-altitude complex in Ladakh.

The hardware is outsized even by global standards:

- About 713 km of HVDC lines, totaling roughly 1,268 circuit-km.

- Two 5 GW HVDC converter terminals, one at Pang in Ladakh and one at Kaithal in Haryana.

- An on-site 12 GWh battery energy storage system co-located with the renewable complex.

The total Phase II cost for this package is pegged at around INR 207.73 billion, or roughly USD 2.5 billion. The central government will shoulder 40% of the capital cost as grant support, with the remaining 60% financed by POWERGRID through a mix of debt and equity.

Timelines are aggressive. The scheme targets commissioning by 2029–30, aligning with India’s broader objective of enabling transmission for 500 GW of renewable capacity by 2030. That target requires not just new lines but smarter, more flexible networks — precisely what this corridor is meant to showcase.

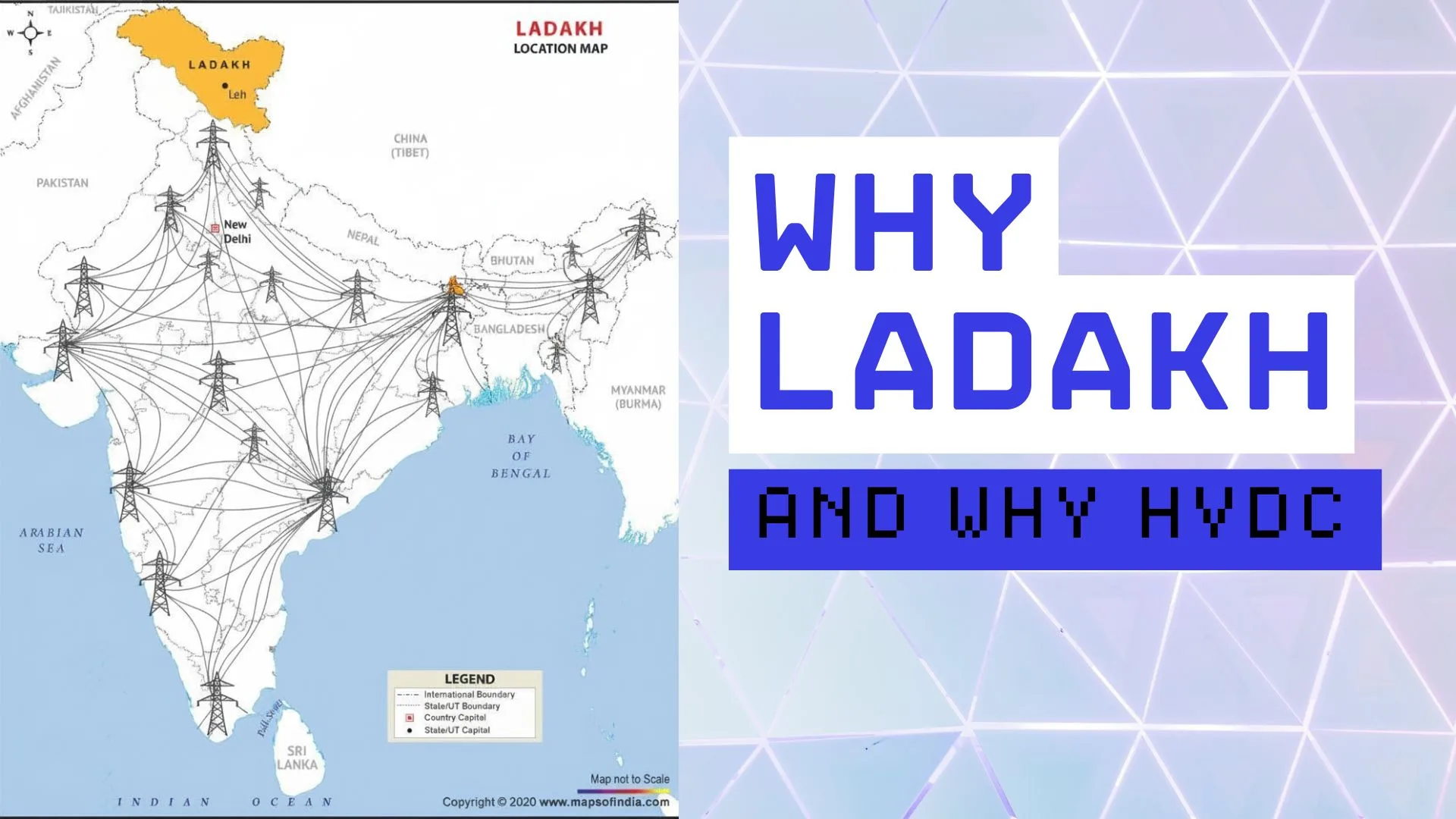

Why Ladakh, and Why HVDC?

Indian map showing ladakh :WireUnwired Research

Ladakh’s appeal is simple: world-class solar irradiance, strong wind resources, and vast tracts of sparsely populated land. Its problem is just as clear: it is far from where India’s power is consumed.

Moving bulk power thousands of kilometers using conventional alternating current (AC) lines would mean higher losses, complex stability issues, and large right-of-way footprints. HVDC changes that equation.

In a typical AC system, power flows oscillate at 50 Hz, which constrains how far you can efficiently and stably transmit large volumes of electricity. HVDC converts that alternating current into direct current at the sending end, moves it over long distances with lower losses and greater controllability, then converts it back to AC near the load centers.

For a remote plateau like Ladakh, that controllability matters. A 5 GW HVDC terminal can modulate power flows precisely, helping stabilize voltage and frequency in receiving regions that are already juggling a rising share of variable renewables.

India has been building HVDC capacity for years, with more than 18,000 MW already in operation across various links.

The 12 GWh Battery: More Than Backup

The attached 12 GWh battery energy storage system is not a bolt-on afterthought. It is the operational hinge on which this project’s value proposition rests.

Variable renewable energy — especially in a harsh, high-altitude climate — can swing sharply within minutes. Without buffering, those swings would stress both the HVDC link and the receiving grids in Haryana and beyond.

A 12 GWh system, depending on its configured power rating, can deliver several gigawatts of output for multiple hours, enabling peak shifting, ramp-rate control, and critical grid services as India’s share of inverter-based generation rises.

The physical line and the battery are only part of the story. The scheme leans heavily on advanced power electronics such as STATCOM-based flexible AC transmission (FACTS) devices and Renewable Energy Management Centres (REMCs) for real-time forecasting and dispatch.

These technologies provide fast reactive power support and data-driven control, which sector studies like IEEFA’s work on green power transmission identify as essential for safely integrating large volumes of renewables into India’s grid.

Filling the Transmission Gap and How It reshapes The National Grid

With India aiming to have transmission capacity in place for 500 GW of renewables by 2030 the renewable energy generation build-out has outpaced transmission expansion in recent years, causing curtailment and stranded assets in states such as Rajasthan.

In response, planners have shifted to potential-based transmission planning and more advanced dispatch models, with the Ladakh–Haryana corridor framed as a dedicated 13 GW evacuation backbone aligned to national 2030 targets rather than a generic line.

This project will help India in many ways

- Geographic diversification: Ladakh’s generation profile differs from Rajasthan and Gujarat, helping reduce correlated weather risk across the system.

- Resource unlocking: The line effectively converts an otherwise remote plateau into a nationally integrated clean-energy hub.

- Flexibility and scalability: HVDC plus storage offers controllable support to weaker regional grids and a template for future remote-resource corridors.

Risks associated with the Ladakh-Haryana Corridor

- Execution risk: Building hundreds of kilometers of line across challenging terrain on a tight schedule.

- Regulatory risk: Designing tariffs that recover costs while keeping power affordable.

- Utilisation risk: Ensuring the full 13 GW renewable complex and the transmission asset are commissioned in sync, given past revocations of grid connectivity for slow-moving projects.

Global Context: One of the Largest of Its Kind and What to Watch Next

Globally, large HVDC links are increasingly used to move remote renewable power, as seen in China’s ultra-high-voltage DC network, Brazil’s Amazon corridors, and emerging European offshore wind hubs.

The Ladakh–Haryana corridor, designed as a multi-gigawatt, renewables-dedicated HVDC line with an integrated 12 GWh storage park, places India among the leading practitioners of such “energy superhighway” concepts.

What to Watch Next

- Route finalisation and clearances: Environmental and land approvals across Ladakh and the northern plains.

- Battery configuration: Final power rating and market role of the 12 GWh storage system.

- Market design: How HVDC and storage flexibility are monetised through capacity, energy, and ancillary service products.

- Coordination with other corridors: Integration with Green Energy Corridor projects so congestion does not simply shift downstream.

Discover more from WireUnwired Research

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.