A security researcher has publicly disclosed a Remote Code Execution (RCE) vulnerability in AMD’s AutoUpdate software after the company dismissed the report as “out of scope” and declined to fix it. The vulnerability allows attackers with network access—whether on local networks or through compromised ISPs—to replace legitimate AMD driver updates with malicious executables that run with user privileges.

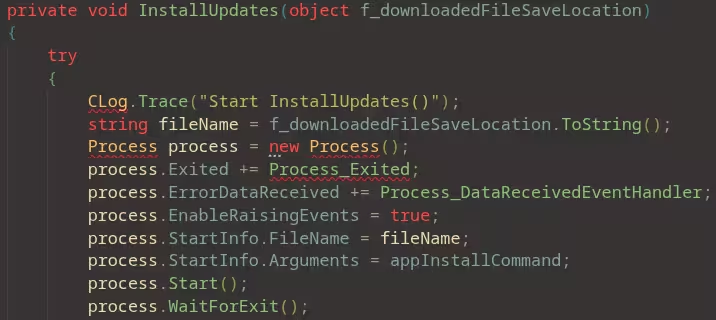

The flaw exists because AMD’s update mechanism downloads executables over unencrypted HTTP connections despite using HTTPS for its initial configuration endpoint. More critically, the software performs no signature verification on downloaded files before executing them, meaning any executable delivered via man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack will run without validation. AMD closed the researcher’s report within hours, stating the issue falls outside their vulnerability disclosure program scope.

This raises uncomfortable questions about how hardware manufacturers handle security in update mechanisms—systems that by design have permission to download and execute code on users’ machines. When a vendor refuses to address a vulnerability that could enable arbitrary code execution, and when that refusal comes not from technical disagreement but from policy definitions of “scope,” the security posture of millions of devices depends on corporate bureaucracy rather than technical merit.

⚡

WireUnwired • Fast Take

- AMD AutoUpdate downloads driver executables over HTTP without signature verification

- Enables MITM attacks to replace legitimate updates with malicious code that executes automatically

- AMD closed security report as “out of scope” within hours—won’t fix despite RCE risk

- Affects all users with AMD AutoUpdate installed—potentially millions of gaming PCs and workstations

The Technical Vulnerability

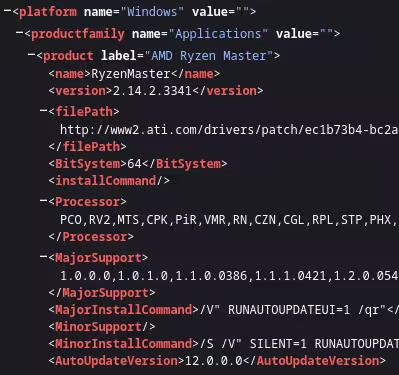

The researcher, investigating why AMD’s AutoUpdate software repeatedly interrupted their gaming sessions with unwanted console windows, decompiled the executable to understand its behavior. The software stores its update configuration endpoint in an `app.config` file, pointing to what appears to be AMD’s development environment URL despite being used in production releases.

While this endpoint uses HTTPS, examining the responses revealed all actual executable download URLs use unencrypted HTTP.

This creates a straightforward attack scenario. An attacker positioned on the victim’s network—whether a malicious actor on public Wi-Fi, a compromised router, or a nation-state with ISP access—can intercept the HTTP download request and respond with a malicious executable instead of AMD’s legitimate driver installer. The AutoUpdate software will then execute this file without performing any validation.

The researcher examined the decompiled code expecting to find signature verification or certificate pinning—standard security practices for update mechanisms. Instead, the software downloads the file specified in the update manifest and immediately executes it with no cryptographic validation. This means the attack requires no exploitation of memory corruption bugs or privilege escalation—just network position and the ability to serve a modified HTTP response.

Attack Scenarios and Risk Assessment

The practical attack surface depends on network positioning. On public Wi-Fi networks, attackers with local access can trivially perform MITM attacks against unencrypted HTTP traffic. Home networks face lower risk unless the router is compromised, but consumer routers frequently run outdated firmware with known vulnerabilities. Corporate networks with proper network security monitoring would likely detect such attacks, but many users run AMD AutoUpdate on personal gaming systems without enterprise-grade protections.

The nation-state threat model, while mentioned in the original disclosure, represents the higher end of risk. Intelligence agencies with ISP access can intercept and modify HTTP traffic at scale, potentially targeting specific individuals or demographic groups. While this requires significant resources, the complete absence of verification makes such attacks undetectable by the victim—the malicious executable appears identical to legitimate update traffic from the victim’s perspective.

The severity stems from the software’s ubiquity. AMD graphics cards power millions of gaming PCs and workstations globally. AutoUpdate typically installs automatically with driver packages, meaning most users have the vulnerable software without explicitly choosing to install update mechanisms. Unlike vulnerabilities requiring user interaction or specific configurations, this flaw is exploitable whenever the update check runs—which can occur automatically on schedule.

AMD’s Response and Industry Context

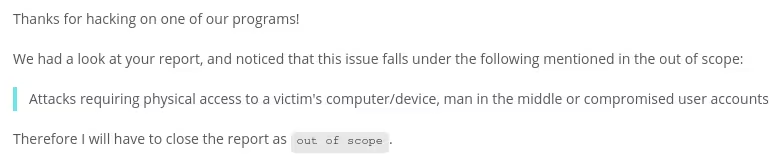

AMD’s decision to close the report as “out of scope” within hours raises questions about their vulnerability disclosure program’s coverage. The timeline is notably brief:

• January 27, 2026: Vulnerability discovered

• February 5, 2026: Reported to AMD

• February 5, 2026: Closed as “won’t fix/out of scope”

• February 6, 2026: Public disclosure

The same-day closure suggests the decision came from policy rather than technical investigation. AMD has not publicly explained why update mechanism security falls outside their vulnerability program scope, particularly when the vulnerability enables arbitrary code execution—typically considered a critical severity issue.

This contrasts with how other hardware manufacturers handle similar issues. NVIDIA, Intel, and Microsoft have all issued security updates for vulnerabilities in their update mechanisms over the past several years, treating such issues as legitimate security concerns rather than out-of-scope configuration choices.

The “out of scope” designation might stem from AMD categorizing this as a software engineering decision rather than a security vulnerability—treating HTTP versus HTTPS as an implementation detail rather than a security control. However, this ignores that update mechanisms are explicitly security-critical systems. They have permission to download and execute code, making their security properties as important as driver code itself.

What Users Can Do

Until AMD addresses this issue—if they ever do—users have limited mitigation options. Uninstalling AMD AutoUpdate removes the vulnerability but also eliminates automatic driver updates, potentially leaving systems without important stability or performance improvements. Manually checking for updates through AMD’s website avoids the vulnerable update mechanism but requires user discipline and doesn’t protect against the same MITM attacks if those downloads also use HTTP.

Network-level mitigations include using VPNs on untrusted networks, ensuring home routers run current firmware, and implementing network monitoring to detect suspicious executable downloads. However, these solutions require technical knowledge beyond most users’ capabilities and don’t address the fundamental problem that trusted software is downloading and executing unverified code.

The broader lesson extends beyond AMD. Update mechanisms represent trusted pathways into systems, making their security paramount. When vendors treat these mechanisms as outside security program scope, they’re essentially declaring that systems designed to download and execute code don’t require the same security rigor as the code itself. That’s a dangerous precedent as software supply chain attacks become increasingly common.

For now, AMD users face a choice: accept the risk from vulnerable update software, abandon automatic updates entirely, or hope AMD reconsiders their position despite explicitly declining to do so. None of these options are satisfactory, and all stem from a vendor decision to classify a straightforward RCE vulnerability as out of scope.

For discussions on hardware security, responsible disclosure, and vendor vulnerability response, join our WhatsApp community where security researchers share real-world vulnerability findings.

Discover more from WireUnwired Research

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.