Vietnam just took a major step toward breaking Asia’s semiconductor stranglehold. For decades, if you wanted chips tested and packaged, you had two choices: send them to Taiwan or South Korea. Both options mean geopolitical risk, long shipping times, and zero control over your supply chain. FPT Corporation just changed that equation by opening Vietnam’s first fully domestic semiconductor testing and packaging facility in Hanoi.

This might sound like yet another semiconductor fab opening but actually its much more than taht. The plant creates Vietnam’s first complete chip supply chain when combined with Viettel’s upcoming fabrication facility. Together, they let Vietnamese companies design a chip, manufacture it, test it, and package it without ever leaving the country. That’s the kind of supply chain independence that nations spend billions trying to achieve—and Vietnam just got there ahead of neighbors like Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

The timing matters enormously. Taiwan Strait tensions make relying on TSMC risky. The 2021 chip shortage showed how a single bottleneck in Asia can halt billions in global production. As countries scramble to “de-risk” supply chains through friendshoring, Vietnam positioned itself as the obvious alternative: politically stable, US-friendly, lower costs than China, and now proven semiconductor capability. FPT’s Phase 2 expansion by 2030 will handle billions of chips annually—enough capacity to matter globally, not just regionally.

⚡

WireUnwired • Fast Take

- FPT opens Vietnam’s first domestic chip testing and packaging facility in Hanoi

- Completes supply chain with Viettel’s fab—design to finished chip entirely in Vietnam

- Phase 2 by 2030: 6,000 sqm facility handling billions of chips annually

- Targets AI edge chips (28-32nm) for IoT, automotive sensors, and drones

What This Facility Actually Does

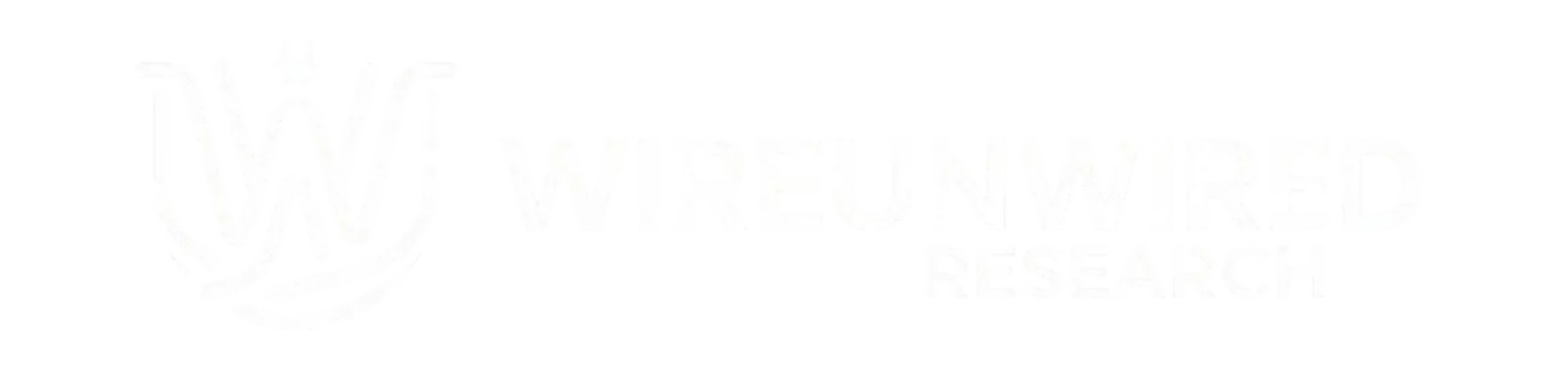

Semiconductor production has three main stages: design, fabrication (making the chips), and testing/packaging (ensuring they work and protecting them for shipment). Most countries can design chips—that’s just software and engineers. Fabrication is exponentially harder, requiring billion-dollar fabs with extreme precision machinery. But even if you can fabricate, you still need testing and packaging, which historically meant shipping wafers to Taiwan’s ASE Technology or similar facilities.

FPT’s new plant handles that final critical step. After Viettel’s fab produces silicon wafers with millions of tiny chips etched onto them, FPT tests each chip for defects, cuts the wafer into individual dies, and packages them into the black squares you see on circuit boards. Think of it like an automotive factory: Viettel builds the engines, FPT tests them and installs them in cars.

The technical focus is AI-on-the-edge chips using 28-32 nanometer process nodes. These aren’t cutting-edge by semiconductor standards—TSMC makes 3nm chips for iPhones—but they’re perfect for the target applications. A 28nm chip offers enough computational power for AI inference (running pre-trained models) in devices like security cameras, automotive sensors, or drone controllers, while consuming minimal power. For a battery-powered IoT sensor that needs to run for years, that efficiency matters more than raw speed.

Phase 1 establishes the basic infrastructure and integration with Viettel’s fab. Phase 2, targeted for 2028-2030, expands the facility to 6,000 square meters with capacity for billions of units annually. This involves advanced packaging techniques like Chip Scale Packaging (CSP), which shrinks the final packaged chip to barely larger than the silicon die itself, and Wafer-Level Packaging (WLP), which packages entire wafers before cutting them into individual chips—more efficient for high-volume production.

Why Vietnam, Why Now

Vietnam’s semiconductor ambitions aren’t new, but they’re accelerating rapidly due to converging factors. The country has spent years building electronics manufacturing expertise through companies like Samsung, which operates major facilities there. This created a skilled workforce and supply chain infrastructure that semiconductors can leverage.

Geopolitically, Vietnam offers what China can’t—US partnership without the baggage of strategic competition. As American companies look to diversify away from China-dependent supply chains (the “China Plus One” strategy), Vietnam emerges as the obvious alternative: lower labor costs than Taiwan or South Korea, political stability, and improving infrastructure. The US-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, upgraded in 2023, explicitly includes semiconductor cooperation.

The 2021 global chip shortage demonstrated the fragility of concentrated supply chains. When Taiwan faced drought-related power issues and COVID disruptions, global electronics production stalled. Automotive manufacturers lost billions because they couldn’t get the relatively simple chips needed for engine controllers and infotainment systems. Companies learned that diversification matters, even if it means slightly higher costs or less cutting-edge technology.

FPT’s facility targets exactly this middle market: chips that don’t need TSMC’s most advanced processes but require reliable, cost-effective production at scale. The billions of IoT devices, automotive sensors, and consumer electronics expected over the next decade mostly use mature process nodes like 28nm—where Vietnam can compete effectively without needing to match Taiwan’s multi-billion-dollar R&D investments in 3nm or 2nm technology.

The Competitive Landscape

FPT isn’t competing directly with TSMC or Samsung on cutting-edge chips. Instead, it’s targeting the Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (OSAT) market, currently dominated by Taiwan’s ASE Technology (controlling about 50% of the market) and a handful of other specialized firms. These companies don’t design or fabricate chips—they just test and package wafers produced by fabs.

Vietnam’s competitive advantages in this market are straightforward: lower labor costs (about 40% less than Taiwan), geographic diversification (reducing Taiwan risk), and improving infrastructure. The disadvantages are equally clear: no track record, unproven yields (the percentage of chips that pass testing), and limited ecosystem compared to Taiwan’s decades of accumulated expertise.

Industry analysts estimate Vietnam could capture 2-3% of the global OSAT market by 2030 if execution goes well. That might sound small, but in a market worth tens of billions annually, it represents significant revenue and positions Vietnam as a credible alternative for companies serious about supply chain resilience.

What Happens Next

The immediate impact centers on Vietnam’s domestic ecosystem. FPT estimates the facility could create 10,000+ jobs and attract $5-10 billion in related investments by 2030 as component suppliers, equipment vendors, and design houses establish local operations. For Vietnamese companies currently importing all their semiconductors, having domestic testing and packaging could reduce costs by 15-20% while dramatically improving supply chain reliability.

Internationally, expect increased investment from companies pursuing China Plus One strategies. Automotive manufacturers, in particular, are desperate for reliable semiconductor supplies after the 2021 shortages cost them billions. Vietnam’s facility targets exactly the kind of chips they need—not flagship smartphone processors but the unglamorous sensors, controllers, and power management chips that modern vehicles require by the hundreds.

The real test comes in 12-18 months as Phase 1 ramps to volume production. Semiconductor manufacturing is unforgiving—yields matter enormously, and new facilities typically start around 70% (meaning 30% of chips fail testing) before improving to industry-standard 90%+ over time. If FPT can achieve competitive yields quickly, it validates Vietnam’s semiconductor ambitions and likely triggers additional investment. If yields disappoint, it confirms skeptics’ concerns that semiconductor manufacturing requires expertise that can’t be built overnight.

FAQ

Q: Why focus on 28-32nm chips instead of cutting-edge technology?

A: These “mature” nodes are perfect for Vietnam’s target markets—IoT devices, automotive sensors, and drones—where power efficiency and cost matter more than raw performance. A 28nm chip can run AI inference for object detection while consuming just 1-2 watts, ideal for battery-powered devices. More importantly, competing at 28nm requires hundreds of millions in investment versus the tens of billions needed for 3nm technology. Vietnam is building expertise in high-volume, cost-sensitive markets before attempting cutting-edge processes—a rational strategy that matches its current capabilities and market opportunities.

Q: How does this compare to India’s semiconductor plans?

A: India announced $10 billion in semiconductor incentives and has multiple fab projects in development, but none have reached production yet. Vietnam’s approach is arguably more pragmatic—FPT is an established tech company with government backing building a testing/packaging facility (less complex than a fab) while partnering with Viettel’s fabrication efforts. India is aiming higher with plans for advanced fabs, but execution risk is also higher. Both countries are pursuing similar “friendshoring” opportunities as Western companies diversify supply chains, so there’s room for both to succeed in different market segments.

Q: What’s the biggest risk to Vietnam’s semiconductor ambitions?

A: Yields and technical execution. Semiconductor manufacturing is brutally difficult—seemingly minor variations in temperature, humidity, or chemical composition can tank production yields. Taiwan’s ASE Technology and other established OSAT providers have spent decades perfecting their processes. Vietnam’s facility needs to achieve competitive yields (90%+ of chips passing testing) within a reasonable timeframe, or customers will stick with proven alternatives despite the geopolitical diversification benefits. The equipment and materials are available globally, but the process knowledge and operational expertise take years to develop. If FPT can hire experienced engineers from Taiwan or South Korea and achieve industry-standard yields by 2027-2028, the venture succeeds. If yields remain stuck at 70-80%, it becomes an expensive lesson rather than a strategic victory.

For real-time updates on semiconductor industry developments, join our WhatsApp community where 2,000+ engineers and industry professionals discuss supply chain shifts and technology trends.

Discover more from WireUnwired Research

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.