Every advanced computer chip in the world—from your iPhone to ChatGPT’s servers—relies on machines made by one Dutch company called ASML. These extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography systems are the only tools capable of manufacturing chips smaller than 7 nanometers, and the U.S. has blocked China from buying them since 2019. That export ban just became significantly less effective.

Reuters reported on January 25, 2026, that Chinese engineers in Shenzhen have activated a working EUV lithography prototype under oversight from China’s Central Science and Technology Commission. The machine isn’t commercially viable yet—yields are around 60% compared to the 90%+ needed for mass production—but it represents a major milestone in China’s decade-long effort to build domestic chip manufacturing capability. If they can scale this technology to production levels by 2028-2030, it would fundamentally reshape the global semiconductor industry.

The timing matters enormously. U.S. export restrictions have tightened progressively since 2019, culminating in sweeping October 2022 rules that cut off China’s access not just to EUV machines but also to advanced chip design software and manufacturing expertise. Those controls assumed China couldn’t develop EUV technology independently for at least another decade. A working prototype in 2026—even an imperfect one—suggests that timeline was overly optimistic. If China achieves chip self-sufficiency by 2030, it eliminates the U.S.’s primary economic leverage while creating parallel, incompatible technology ecosystems that will cost the industry hundreds of billions to maintain.

⚡

WireUnwired • Fast Take

- Chinese engineers activated an operational EUV lithography prototype in Shenzhen, confirmed by Reuters

- Current 60% yield rate makes it unsuitable for commercial production, but proves technical feasibility

- Timeline for China’s chip independence accelerates from 2035 estimates to potential 2028-2030 reality

- Global semiconductor industry faces fragmentation into Western and Chinese technology ecosystems

The Full Story: What Just Happened

Reuters broke the story on January 25, 2026, citing sources with direct knowledge of the Shenzhen facility and documentation from China’s Central Science and Technology Commission, the government body coordinating the country’s most sensitive technology projects. The prototype EUV machine has successfully exposed silicon wafers with patterns at the 5-7 nanometer scale, demonstrating that Chinese engineers have solved the fundamental physics and engineering challenges that make EUV lithography so difficult.

The context makes this significant. EUV lithography works by generating extreme ultraviolet light at 13.5 nanometer wavelengths—light so energetic it gets absorbed by air, requiring the entire system to operate in a vacuum. ASML spent over €8 billion and more than 20 years perfecting this technology, solving problems like how to generate and focus EUV light (which no natural materials can reflect efficiently) and how to synchronize thousands of components to nanometer-scale precision while moving at high speeds.

U.S. export controls specifically targeted the components China would need to build such a machine. German company Zeiss makes the ultra-precise mirrors. U.S. company Cymer (owned by ASML) provides the powerful lasers. Dozens of other Western suppliers contribute specialized optics, control systems, and measurement equipment. The export ban was designed to make it nearly impossible for China to assemble a complete EUV system from domestic components alone.

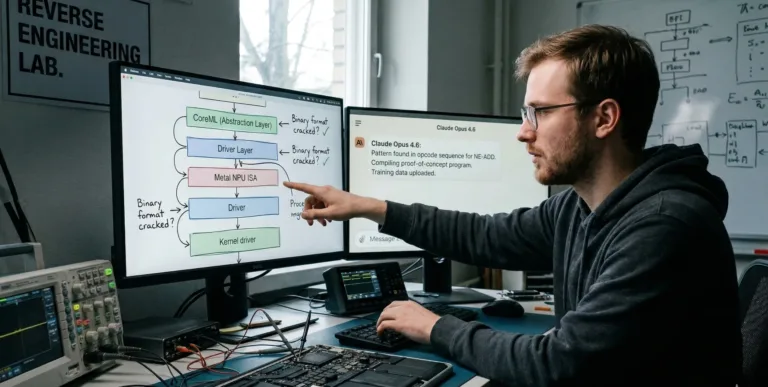

The Shenzhen prototype apparently bypasses these restrictions through a combination of domestically developed alternatives and what sources describe as “hybrid architecture”—using different technical approaches where Western components aren’t available. The machine reportedly uses Chinese-made lasers (likely developed from military laser programs) and domestically manufactured mirrors, though with lower precision than ASML’s Zeiss optics. Most critically, it incorporates AI-powered error correction algorithms to compensate for mechanical imperfections that Western machines solve through ultra-precise hardware.

The reported 60% yield rate—meaning 60% of chips produced work correctly—confirms this is still prototype-level technology. Commercial chip manufacturing requires yields above 90% to be economically viable. For context, when TSMC first adopted ASML’s EUV machines around 2018, they spent two years optimizing processes to achieve commercial yields. China faces a similar learning curve, but the existence of a working prototype means they’ve cleared the highest technical hurdles.

Technical Breakdown: How EUV Lithography Works

To understand why this matters, you need to know what EUV lithography does and why it’s so hard to build. The technology patterns features on silicon wafers by projecting circuit designs using extremely short-wavelength ultraviolet light—13.5 nanometers, about 1/15th the wavelength of visible light. Shorter wavelengths allow smaller features, which is why EUV enabled the jump from 7nm chips to 5nm, 3nm, and eventually 2nm.

The core challenge is generating EUV light. ASML’s machines do this by firing high-powered CO2 lasers (around 20 kilowatts) at tiny tin droplets traveling at 50,000 kilometers per hour—about 40 times the speed of sound. When the laser hits the droplet, it vaporizes into plasma exceeding 200,000°C, briefly creating a miniature sun that emits EUV photons. This happens 50,000 times per second.

Those EUV photons then bounce off a series of mirrors—typically 10-14 mirrors, each coated with alternating layers of molybdenum and silicon just a few nanometers thick. Normal mirrors can’t reflect EUV light; you need these specialized multi-layer coatings, and they must be polished to within 0.1 nanometer precision. Even atomic-scale roughness causes scattering that ruins the image. Zeiss pioneered these mirrors, which is why the U.S. pressured Germany to block their export to China.

The Shenzhen prototype reportedly solves the mirror problem through lower-precision optics combined with computational correction. Instead of achieving near-perfect mirror surfaces (extraordinarily difficult), Chinese engineers apparently use sensors to measure imperfections in real-time and adjust the exposure dose and timing to compensate. Think of it like stabilizing a handheld camera photo through software image processing rather than building a perfect mechanical stabilizer. It’s not as good as the hardware solution, but it works well enough to prove the concept.

The wafer stage—the platform that holds and moves the silicon wafer during exposure—must position with nanometer accuracy while scanning at speeds up to 7 meters per second. ASML uses decades of precision engineering expertise here. Reports suggest China’s prototype leverages quantum gyroscopes and inertial sensors developed for space applications (their lunar landing program) to achieve similar precision through different means.

Current throughput reportedly reaches 150 wafers per hour, compared to ASML’s latest machines at 200+ wafers per hour. For commercial production, this is acceptable—the bigger problem is the 60% yield. That number needs to climb above 90% before any chipmaker would use this for production. But yield improvements typically come from process optimization and iteration, not fundamental breakthroughs. If China can get prototype machines into SMIC’s fabs (their leading foundry) for real-world testing, yields could improve rapidly.

Competitive Landscape: Technology Gap Assessment

The global semiconductor equipment market has effectively split into tiers, with ASML dominating the absolute cutting edge.

| Technology | ASML (West) | China Prototype | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smallest Node | 2nm (High-NA EUV) | 5-7nm (Standard EUV) | ~3 years behind |

| Throughput | 200+ wafers/hour | ~150 wafers/hour | 25% slower |

| Yield Rate | 90%+ (production) | ~60% (prototype) | Not viable yet |

| Machine Cost | ~$200M each | Unknown (est. $100M) | Potentially cheaper |

| Commercial Status | Mass production | R&D prototype only | 2-4 years to production |

The table reveals both progress and limitations. China has demonstrated they can build a machine that technically functions, but it’s not yet competitive with ASML’s commercial systems. However, the gap is narrower than most Western analysts expected. Many industry observers predicted China wouldn’t have even a prototype EUV system until 2028-2030 at earliest. Having one operational in early 2026 suggests either faster-than-expected domestic development or successful acquisition of restricted technology through indirect channels.

For context, ASML shipped 61 EUV systems in 2025 and has a backlog of over 90 orders worth more than €13 billion. Every leading-edge chip fab in the world—TSMC, Samsung, Intel—depends entirely on ASML machines. If China can field even technologically inferior domestic alternatives by 2028, it breaks this dependency for the Chinese market, which represents roughly 20-25% of global semiconductor demand.

Market Impact: What Changes Now

The immediate financial impact centers on uncertainty and strategic repositioning. ASML’s stock dropped approximately 3-4% on the Reuters report—not catastrophic, but significant for a company with €280 billion market capitalization. The market is pricing in the possibility that China’s captive domestic market (currently about €6-8 billion annually for ASML) could eventually transition to domestic equipment, even if that equipment is technically inferior.

For Chinese chipmakers like SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation), this represents potential long-term salvation. SMIC currently operates at technological disadvantage, unable to manufacture chips below 7nm because they can’t access EUV machines. If domestic EUV becomes available by 2028, even with lower yields and throughput, SMIC could begin producing 5nm chips for the Chinese market. That wouldn’t match TSMC’s 3nm or incoming 2nm nodes, but it’s good enough for most applications—smartphones, automotive chips, servers, and consumer electronics.

The broader strategic implication is market fragmentation. The semiconductor industry has operated as a genuinely global market for decades, with designs flowing from the U.S., manufacturing happening in Taiwan and Korea, equipment coming from the Netherlands and Japan, and materials sourced worldwide. That integration created efficiency but also interdependence. A Chinese domestic EUV capability—even a mediocre one—enables a parallel ecosystem: Chinese-designed chips, made on Chinese equipment, in Chinese fabs, serving the Chinese market.

This bifurcation carries enormous costs. Companies like Apple, Qualcomm, and Nvidia that sell globally would need to maintain separate supply chains—Western chips for Western markets, Chinese chips for Chinese markets. Development costs roughly double. Testing and qualification multiply. Some analysts estimate the industry could spend an additional $300-500 billion over the next decade building redundant parallel infrastructure, compared to the integrated global model.

The geopolitical dimension is equally significant. U.S. export controls on semiconductors represent one of the few sources of economic leverage over China. If those controls become ineffective because China develops domestic alternatives, American negotiating power in disputes over Taiwan, trade, or technology standards diminishes substantially. Conversely, from China’s perspective, achieving chip self-sufficiency eliminates a critical strategic vulnerability.

Timeline expectations need revision. Most U.S. policymakers assumed export controls would maintain Western technological advantage through at least 2035, giving time to build up domestic manufacturing capacity through CHIPS Act investments. If China reaches commercial-grade EUV production by 2028-2030, that timeline compresses dramatically. Intel’s new Ohio fab and TSMC’s Arizona facility need to ramp faster than planned.

Expert Take: Industry Reactions

Semiconductor analysts are divided on the significance. Dan Hutcheson, vice chair of TechInsights (a leading semiconductor analysis firm), cautioned in a briefing note: “A prototype that works in a controlled lab environment is very different from a production system that needs to run 24/7 with 90%+ yields. China has demonstrated technical capability, which is impressive, but the engineering challenges of scaling this to commercial production shouldn’t be underestimated. ASML spent years moving from prototype to production.”

However, Dylan Patel of SemiAnalysis, known for detailed technical breakdowns of Chinese semiconductor progress, views the timeline as more aggressive: “The fact that they have a working system at all in 2026 means we significantly underestimated their capability. If they’re achieving 60% yields on a prototype, getting to 80-85% yields for domestic market production—which doesn’t need to match TSMC’s standards—could happen within 18-24 months. That’s 2028, not 2035.”

ASML declined to comment specifically on the Reuters report but issued a statement noting that “EUV lithography represents decades of collaborative innovation across hundreds of suppliers in multiple countries. Independent development of comparable systems faces substantial technical and supply chain challenges.” Reading between the lines, ASML doesn’t view this as an immediate competitive threat but acknowledges it’s a significant development.

TSMC executives speaking at industry conferences (not specifically referencing the China prototype) have emphasized that leading-edge chip manufacturing depends on entire ecosystems, not just lithography equipment. “Even if you have an EUV machine, you need complementary etching equipment, deposition systems, metrology tools, and process expertise. Those take years to develop,” noted one TSMC vice president. The implication: China faces many more hurdles beyond EUV alone.

U.S. government officials have been notably quiet, likely assessing the intelligence implications. The Commerce Department, which administers export controls, may face pressure to tighten restrictions further or expand them to additional categories of equipment. However, each tightening risks accelerating Chinese domestic development while harming American equipment companies’ revenues—a difficult balance.

FAQ

Q: Is this Chinese EUV machine producing chips for smartphones or computers right now?

A: No. The prototype is operational for research and testing but has yields around 60%—meaning 40% of chips it produces don’t work. Commercial chip manufacturing requires yields above 90% to be economically viable. At current performance levels, using this machine for actual production would be prohibitively expensive. The significance is that it proves China has solved the fundamental technical challenges; improving yields is difficult but primarily requires iteration and process optimization rather than new breakthroughs. Most analysts expect 2028-2030 before Chinese EUV systems reach commercial production quality.

Q: Does this mean China no longer needs to buy chips from Taiwan or the West?

A: Not yet, and not entirely even when this technology matures. First, it will take years to scale from prototype to production-grade systems. Second, even if China achieves commercial EUV production by 2028, they’ll likely be making 5nm chips while TSMC is at 2nm or beyond—a meaningful performance gap. China will still depend on imports for the most advanced chips used in cutting-edge applications like AI training or high-end smartphones. However, for most consumer electronics, automotive chips, and general computing, 5nm technology (circa 2020 performance level) is sufficient. This would allow China to meet perhaps 60-70% of domestic demand with indigenous technology, versus less than 30% currently.

Q: What does this mean for U.S. export controls and the CHIPS Act?

A: It suggests the export control strategy, while slowing China’s progress, hasn’t stopped it entirely. U.S. policy assumed maintaining a 10-15 year technology lead through equipment restrictions. If China reaches commercial EUV capability by 2028-2030, that lead narrows to perhaps 3-5 years—still significant but less commanding. This likely accelerates urgency around the CHIPS Act’s domestic manufacturing initiatives. Intel’s Ohio fab and TSMC’s Arizona facility become more strategically critical if they can’t rely on export controls alone to maintain Western advantage. Expect potential new rounds of restrictions targeting even more equipment categories, though each expansion risks pushing more of China’s supply chain toward domestic alternatives, potentially backfiring long-term.

For real-time updates on semiconductor industry developments, join our WhatsApp community—where 2,000+ founders and engineers discuss what’s actually happening in tech.

Discover more from WireUnwired Research

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.