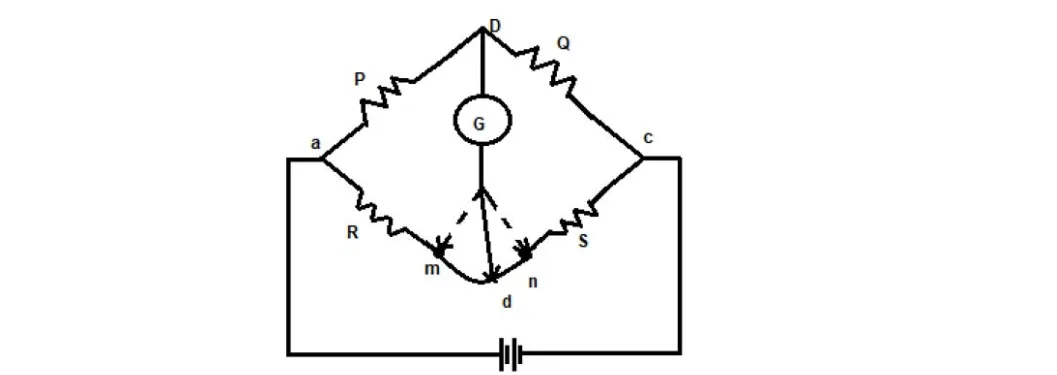

For over a century, semiconductor engineers have relied on a measurement technique so elegant it seemed unbreakable. Kelvin measurement—named after Lord Kelvin, who developed it in the 1860s—solved a fundamental problem: how do you measure the electrical resistance of something without the measurement itself interfering with the result? The answer was simple. Use four wires instead of two. Drive current through one pair, measure voltage through another, and the resistance of your test leads magically cancels out.

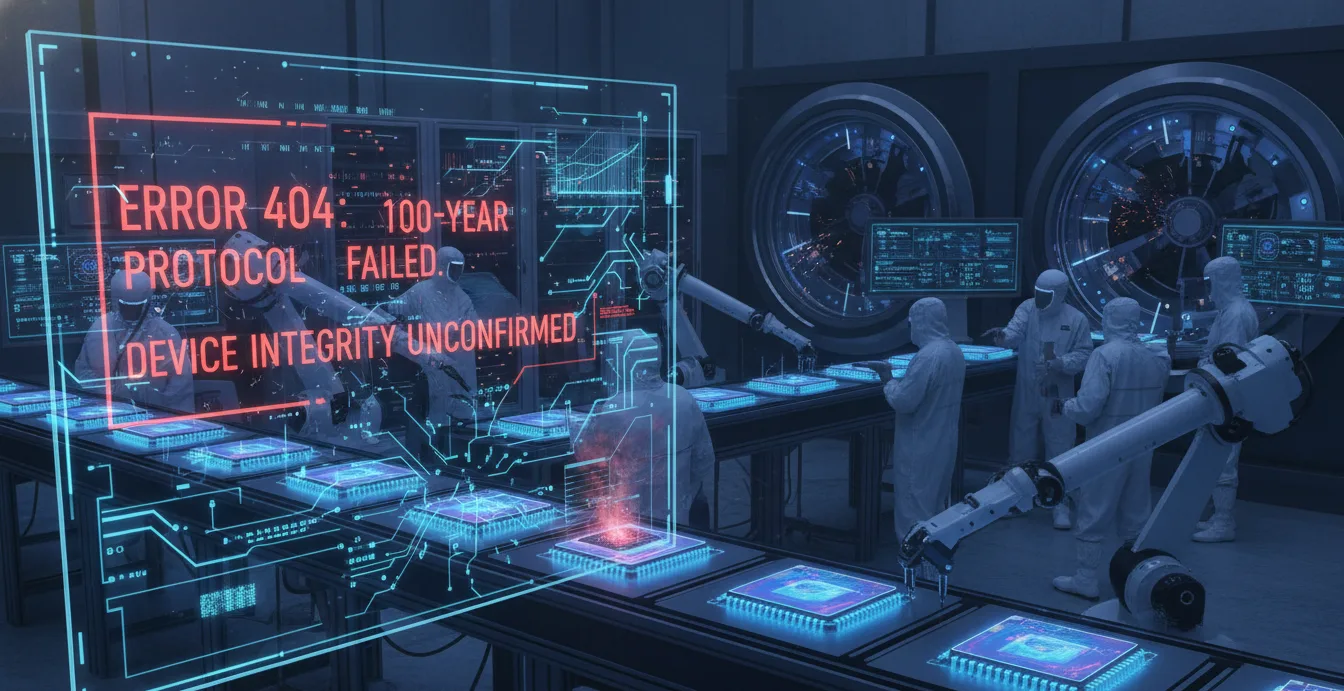

It worked flawlessly for generations. Then advanced chip packaging arrived, and the 100-year-old technique just stopped working.

The problem isn’t that the physics changed. Ohm’s Law still applies. Resistance is still voltage divided by current. What changed is where resistance actually lives in modern chips. It used to concentrate inside transistors—neat, measurable, predictable. Now it spreads across interfaces between stacked dies, microbumps connecting chiplets, and redistribution layers routing signals through 3D structures. By the time engineers measure resistance at final test, they’re often measuring the wrong thing entirely.

“In advanced packages, the most common failures are marginal resistance-driven effects in the interfaces that are still within spec initially, but drift with thermal cycling and real use,” says Nir Sever, senior director at proteanTecs. “Microbump degradation is a good example. You can pass all the standard tests, yet still have a connection that’s slowly losing integrity. It only becomes obvious when you track it continuously and see the degradation trend.”

This fundamentally changes what resistance measurement means. It’s no longer a pass/fail check at the end of production. It’s a signal that must be tracked across time, across manufacturing steps, and across physical boundaries—or it becomes meaningless.

⚡

WireUnwired • Fast Take

- Kelvin measurement—used for 100+ years—assumed resistance lived inside components, not at interfaces between them

- Advanced packaging (chiplets, 3D stacking) distributes resistance across connections that change with temperature, stress, time

- Traditional end-of-line testing now catches problems too late—after $25K worth of dies are assembled

- “Kelvin Everywhere” approach: continuous monitoring across manufacturing rather than single-point testing

The old Kelvin method made four assumptions that seemed obviously true for so long that nobody even mentioned them. First, it assumed the chip itself was what you were measuring—not all the stuff connecting to it. Second, it assumed the contact points where your test probe touches the chip either didn’t add much resistance, or added the same amount every time. Third, it assumed testing didn’t change what you were measuring. Fourth, it assumed resistance stayed in one place and didn’t move around.

Modern chip packaging breaks all four of these assumptions. The contact points aren’t simple anymore—they’re complex mechanical connections that can wear out, get dirty, or shift under pressure. The “chip” isn’t one piece of silicon anymore. It’s multiple chips stacked like a layer cake, connected through thousands of microscopic solder bumps, with power having to travel from the bottom layer all the way to the power-hungry processor at the top. Even pressing a test probe against the chip can change the very connection you’re trying to measure.

“What people call noise is usually variation in the interconnect resistance itself,” explains Jack Lewis, CTO at Modus Test. “It’s not electrical noise. It’s the resistance of the connection changing from one test insertion to the next. The magnitude of that change is often bigger than anything happening in your actual silicon.”

This creates a serious money problem. High-end AI chips are expected to cost $25,000 each by 2030. Each one contains multiple expensive chips that can’t be separated once they’re glued and soldered together. If a connection problem only shows up at the final test—after all those expensive pieces are permanently assembled—the entire package is garbage. Companies can’t afford to throw away $25,000 worth of chips because a microscopic connection went bad in a way the old testing method didn’t catch.

The solution emerging across the chip industry is called “Kelvin Everywhere.” It doesn’t mean literally putting test probes everywhere. It means taking Kelvin’s core idea—keep your measurement separate from what you’re measuring—and applying it throughout the entire manufacturing process, not just at the end.

In practice, this means measuring resistance constantly, not just once. It means tracking how resistance changes when the chip heats up and cools down, when it’s stressed during assembly, and when it’s tested multiple times. It means comparing measurements taken early in production with tests done at the end, so you can catch problems before expensive chips are permanently stuck together. And it means putting tiny sensors directly inside chips to monitor connections while the chip is actually running, not just sitting on a test bench.

“Many failure precursors are no longer well-represented by a static resistance number at a single test point,” says Sever. “Embedded monitoring provides continuous observation of what really matters—functional margin under real stress conditions.”

This approach exposes problems that traditional testing misses entirely. A connection might measure acceptable resistance when tested cold, then degrade under thermal cycling during normal use. Microbumps can pass pattern tests but slowly lose integrity under real traffic patterns. Interfaces between materials can drift over time in ways that only become visible when tracked continuously across the device’s operating life.

The hard part is telling the difference between real problems and false alarms. Modern test equipment can detect tiny resistance changes—just a few thousandths of an ohm. But those tiny changes exist alongside bigger variations from things like test probes that don’t make perfect contact every time, temperature differences, and mechanical wobbles. More data doesn’t automatically give you better answers—it can just give you more confusion if you don’t know how to interpret it.

“Make sure your test setup is as good as it can be,” warns Lewis. “Test equipment problems can create so much noise in your data that it becomes impossible to see what’s actually happening in the chip versus what’s happening in your test rig.”

This is where computer analysis becomes crucial. A single measurement doesn’t tell you much when resistance is spread across multiple connections. What matters is patterns: how resistance behaves over time, how it responds to heat, and how today’s measurement compares to measurements from last week. Machine learning can spot degradation patterns, but only when it has enough good data and someone who understands the physics validates the results.

The toughest challenges might not be technical. Kelvin Everywhere requires different teams—chip designers, testers, and factory workers—to work together closely when they’ve historically done their jobs separately. It requires spending money on data systems and analysis tools that don’t immediately increase production. Most companies are good at either understanding their manufacturing process deeply or collecting lots of historical data, but rarely both.

Still, the need is clear. Resistance doesn’t live where it used to—neatly packaged inside individual components that could be tested cleanly. It’s scattered across connections, changes with temperature and stress, and shifts over time. The 100-year-old Kelvin technique still provides the basic math, but how we use it must evolve. The future isn’t building better test probes or more sensitive meters. It’s treating resistance as something that needs to be watched and understood continuously throughout the entire manufacturing process, not just checked once at the end.

For discussions on semiconductor testing, advanced packaging challenges, and chip manufacturing, join our WhatsApp community where engineers share insights on emerging fab technologies.

Discover more from WireUnwired Research

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.